|

|||||||||||||||

|

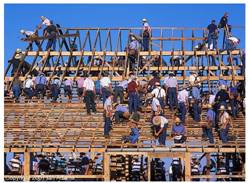

What is social production of habitat? Social production of habitat is an international term, most commonly in Latin America, that refers to the process and product arising from a community collectively determining and creating the conditions of its own living environment. In impoverished and marginalized communities, these relations in producing the living environment are essential for their survival, development and ultimate prosperity. Therefore, social production of habitat is a participatory development process that can—and does—happen everywhere.

Much of what are today considered as examples of “social production of housing” or, more broadly, ”social production of habitat,” are popular alternatives to the failed housing policies of the 1960s and 1970s.[1] Social production is present when people take the initiative to pose solutions to the shared problems of their material world. Partners in social production of habitat primarily involve the concerned community acting in some kind of formal or informal bond. The social production of habitat (SPH) actors also could include organizations and/or other actors external to the community, such as technical experts, social organizers, NGOs, donors, private sector enterprises, professional associations, academics or government institutions, or any combination of these. However, at the heart of social production is the people’s agency on some collective scale, which is commonly referred to as the basic ingredient of social movements. Many social-production experiences, as social movements generally, begin as individual actions and initiatives, rather than organized multiparty programs or projects. However, social production of habitat (SPH) becomes apparent with the convergence of efforts and interests that reflect the collective character and needs of a community. Hence, one proposed definition of SPH emphasizes the planned, participatory and strategic characteristics, including: § Active protagonists inclined to link with others in a flexible planning process, § Participatory decision making that includes the whole of the actors, § Diagnosis of problems based upon a agreed expression of needs, § Projects that express a collective sense of what is possible § Consensus building and conflict resolution processes, and § Collective construction and implementation of action plans.[2] In economic terms, social production involves people joining together and relying on themselves and each other to produce a good or service. In doing so, they identify, exploit and increase social capital as a developmental asset. The processes and outcomes of social production manifest despite—or because of—a lack of local finance capital concentration. It takes place with the awareness that monetary capital is concentrated elsewhere, which is increasingly the case in our globalizing world. Therefore, SPH processes find community members and partners contributing labor, time, materials and/or money (e.g., through savings schemes) from within the group to build community assets in the form of housing, infrastructure, services, environmental improvements, or other achievements that redound to the benefit of the local initiators/participants. Social production of habitat is a process (and product) that identifies, exploits and further develops relationships within the community (social capital). Mobilizing these productive relationships could mean identifying existing collectives of women, men, students, unionized workers, fisherfolk, extended families, coreligionists, professional associations, etc. who could facilitate the process of identifying, exploiting or building social capital used in producing the desired results. The process and outcomes typically bring about social transformation toward local democratization, enabling a

From another perspective, social production means collective action to satisfy human needs and, thus, realize human dignity and fairness as a human right. The human rights dimension of SPH emerges with an awareness of actual entitlements that the people in the community can claim for themselves and others, and not just a privilege to be granted to some. Essential to social production of habitat, from a human rights perspective, are the obligations of the State that arise from its ratification of international human rights treaties and adoption of compatible local law. Human rights include the entitlement of everyone to enjoy a clean living environment, reside in adequate housing, benefit from an equitable distribution and use of land, access sufficient food and water, live with reasonable access to sources of livelihood, be assured of personal security, be protected from forced eviction, participate in decisions affecting one’s living space, engage in alternative planning as a means to assert the right to remain and obtain formal recognition, and have enough reliable information to achieve all of the above. Greater gender equality features as both a means and an end of social production, owing to its participatory nature. When considering the dimensions of social production, many other benefits come into view, not least of these include the psychological effect of improved motivation and self-worth. Additional to this is the cultural dimension that reclaims the rights of the community to demonstrate its artistic production reflecting the totality of socially transmitted behavior patterns, aesthetic creations, beliefs, institutions, or other products of community activities work.[3] The political dimension involves people demanding that the relevant authorities and powers facilitate—or, at least, not hinder—the participatory decision making and popular actions. Naturally, of course, the right to development (a construct of all individual and collective human rights) is intrinsically linked to the social production process, with or without the support and participation of government institutions, programs, policies or budgets. The guiding tools of civilized statecraft found in international public law call for States to respect, defend, promote and fulfill human rights, including the human right to adequate housing. That implies that States and governments bear a duty to enable social production through policies, programs, institutions, legislation, budgets and a variety of services. States and governments hold the corresponding duty to refrain from actions that impede social production, such as forced eviction, confiscation and repression of housing rights defenders, discrimination, corruption, privatizing public goods and services and other violations. Social production of habitat epitomizes people’s agency to improve living conditions, but does not absolve the States and governments of their treaty-bound obligations to citizens and residents. (For a discussion of the linkages between SPH and the human right to adequate housing, click on the “SPH and HRAH” button above.) The effects of neoliberal policies and economic globalization include the privatization of social goods, the concentration of capital in fewer hands, the withdrawal of States and governments from public service provision, and ever-deepening poverty. This makes social production an increasingly important set of practical strategies in the struggle for social justice both locally and globally. In this connection, SPH has acquired an additional meaning. The “social” aspect of the production of habitat may imply an essentially popular or informal character, especially given the term’s habitual usage in the Latin American context. It also assumes that, in the SPH process, the community also realizes a kind of “social distribution” of the goods and values that they produce. This suggests that those dedicating their time, labor and materials are also the direct consumers of the output. In the terms of social science theory about productive relations, that means that the SPH process does not envision other intervening parties collecting “surplus value” from the product in the case of its exchange as a commodity. In this sense of “social” production and distribution of the habitat, the fruits of the collective efforts at improving facilities, the living space and living conditions, as well as the enhanced social capital remain as assets fully within the productive community.

SPH and HIC Middle East/North Africa After long engagement with the practice of SPH, Habitat International Coalition (HIC) and InWent developed the Social Production of Habitat Project in 2003 as a problem-solving initiative to collect, understand and exchange these strategies on the regional and global levels. The HLRN publication, Anatomies of a Social Movement,[4] already has provided many lessons.

The civil society of the Middle East/North Africa is one the most isolated of any region, but especially from the global experience of social movements that have become so closely identified with SPH. The reasons of this relative estrangement are the subject of needed inquiry in other forums. However, suffice it to say that none of the reasons are good ones. They tend to create a self-fulfilling prophecy that says the region has few like-minded partners and even fewer opportunities for popular initiative. The HLRN’s catalog of SPH experiences in the cultural unit known as Middle East/North Africa has shed new light on the under-reported social movements and the common assumptions about the authoritarian nature of States in the region. In so far as social movements contribute to democratization, these cases—and others—demonstrate that homegrown nature of democratization, and that the humanizing process of democracy does not necessarily depend upon designs from abroad. In May–June 2004, the Housing and Land Rights Network of HIC convened the first regional workshop with members and other agents of social production of habitat through its coordination office in Cairo. Those participants—and a subsequently widening circle of others—have come forward with a diversity of experience that defies generalization. The social production experiences of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine/Israel and Syria compiled here involve sanitation, environmental protection, refugee relief and slum upgrading in their fields of service. They confront the State, or cooperate with the State, depending on local circumstances. In any case, these vignettes of applied people’s agency each reveal important lessons about the nature of the State concerned, including the potential for cooperation of civil society with local and central authorities. In a region so plagued with continuing colonization, wars of aggression, conservatism and maldistribution of resources, the essential message arising from the present collection of experiences at social production of habitat in the Middle East/North Africa is a resounding note of hope and encouragement arising from the people. [1] See Eike Jakob Schultz, “Stones in the Way: On Self-determination in Housing in Times of Globalization,” Trialog: A Journal for Planning and Building in the Third World, no. 78 (March 2003), pp. 5–7; Gustavo Romero, “Social Production of Habitat: Reflections on Its History, Conceptions and Proposals,” Trialog, op cit., pp. 8–15. [2] Adapted from Gustavo Romero, op cit., p. 15. [3] See reference to the social production of culture above, in “Concept and History” of social production?” [4] Anatomies of a Social Movement: Social Production of Habitat in the Middle East/North Africa, Part I (Cairo: HIC-HLRN, 2004). |

Social Production of Habitat

© 2021 All rights reserved to HIC-HLRN -Disclaimer