|

||||||||||||

|

Social Capital: |

||||||||||||

|

A Crucial Concept in Understanding Social Production |

||||||||||||

|

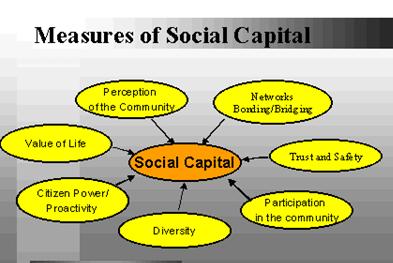

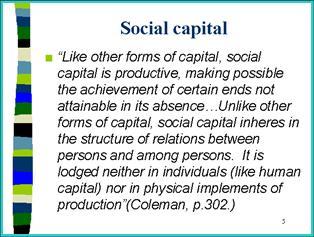

Compilation and comments by Murielle Mignot Relations within social networks that allow mutual support constitute social capital, and social production represents the processes and results of these specific relations in action. Thus, both concepts are intrinsically related, and understanding the nature and function of social capital is essential to envision fully what social production can achieve. However, while a whole theoretical school of thoughts has grown up around the concept of social capital, a more empirical approach that accumulates testimonies on social production may help to place the social capital concept in a critical perspective and an organic context. Note: The first four sections and the readings list constitute a selection of excerpts from the Saguaro Seminar, World Bank Group, and Encyclopedia of Informal Education (Infed) webpages. Section 5 is a basic critical analysis of these pages, not comprehensive but designed to raise questions on the definitions of social capital previously reported. 1. Definition The concept and theory of social capital dates back to the origins of social science; however, recent scholarship has focused on social capital as a subject of social organization and a potential source of value that can be harnessed and converted for strategic and gainful purposes. According to Robert David Putnam, the central premise of social capital is that social networks have value. Social capital refers to the collective value of all "social networks" and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other. Social capital refers to the institutions, relationships, and norms that shape the quality and quantity of a society`s social interactions. Increasing evidence shows that social cohesion is critical for societies to prosper economically and for development to be sustainable. Social capital is not just the sum of the institutions that underpin a society; it is the glue that holds them together However, social capital may not always be beneficial. Horizontal networks of individual citizens and groups that enhance community productivity and cohesion are said to be positive social capital assets whereas self-serving exclusive gangs and hierarchical patronage systems that operate at cross purposes to communitarian interests can be thought of as negative social capital burdens on society. 2. History of the research on the concept Robert David Putnam, if not the first one to write on the issue, is considered as the major author on the concept of social capital. He is a U.S. political scientist and professor at Harvard University, and is well-known for his writings on civic engagement and civil society along with social capital. However, his work is concentrated on the United States only. His most famous (and controversial) work, Bowling Alone, argues that the United States has undergone an unprecedented collapse in civic, social, associational, and political life (social capital) since the 1960s, with serious negative consequences. Though he measured this decline in data of many varieties, his most striking point was that virtually every traditional civic, social, and fraternal organization had undergone a massive decline in membership. From his research, a working group has formed at Harvard University and is called Saguaro Seminar. Most definitions around the social capital concept, notably those used by the World Bank, come from Putnam’s work and this research. 3. Measuring social capital The Saguaro Seminar, in the continuation of Putnam’s work, has been elaborating various means to measure the level of social capital in different contexts. It says on its website that measurement of social capital is important for the three following reasons: (a) Measurement helps make the concept of social capital more tangible for people who find social capital difficult or abstract; (b) It increases our investment in social capital: in a performance-driven era, social capital will be relegated to second-tier status in the allocation of resources, unless organizations can show that their community-building efforts are showing results; and (c) Measurement helps funders and community organizations build more social capital. Everything that involves any human interaction can be asserted to create social capital, but the real question is does it build a significant amount of social capital, and if so, how much? Is a specific part of an organization’s effort worth continuing or should it be scrapped and revamped? Do mentoring programs, playgrounds, or sponsoring block parties lead more typically to greater social capital creation? The working group has undertaken the following measurement activities: 1. Social Capital Community Benchmark Survey: In 2000, we conducted the largest-ever survey on the civic engagement of U.S. Americans, in partnership with nearly three-dozen community foundations (and other funders). Nearly 30,000 respondents were surveyed in 40 communities across 29 states. For more information on this survey follow this link: http://www.ksg.harvard.edu/saguaro/communitysurvey/index.html 2. Social Capital Short-form Survey: Based on the 2000 survey and other surveys in 2001/2002, the Saguaro Seminar has distilled down the 25–minute Social Capital Community Benchmark Survey into a Short Form that has 5–10 minutes of questions. 3. Social capital toolkit: The Saguaro Seminar has developed a framework for how community leaders and others should think about efforts to build local social capital. 4. Program evaluation guide: The Program Evaluation Guide is intended for nonprofit organizations, businesses, or other entities that want to examine the social capital impact of their work. It is less directive than the Social Capital Short Form Survey in suggesting the questions one should use and which respondents one should survey. See the website at: http://www.ksg.harvard.edu/saguaro/evaluationguide.htm. 5. Social capital impact statement: The working group has spent some time into trying to think about the social capital impact of various actions (prospectively): http://www.ksg.harvard.edu/saguaro/impactstatement.htm 4. Related concepts (a) Civil society and social capital Social capital within a nongovernmental organization (NGO) Trust and willingness to cooperate allows people to form groups and associations, which facilitate the realization of shared goals. Grameen Bank (Bangladesh) lends money to rural poor, especially women, at a daily loan volume of $1.5 million and has a 98% repayment rate. The organization was started in 1976 by Muhammad Yunus, who lent money to 42 persons, because he trusted they would repay it. Since then members have developed rules to maximize repayment of loans, but trust still plays a critical role in the organization’s success, particularly in the absence of collateral (Uphoff, Esman and Krishna, 1997). Social capital and civil society can promote welfare and economic development When the state is weak or not interested, civil society and the social capital it engenders can be a crucial provider of informal social insurance and can facilitate economic development. Six-S (Burkina Faso) is a loose federation of rural organizations supported by more formal international NGOs. Social capital has helped Six-S to mobilize over 1 million villagers in 1,500 communities in West Africa in an effort to create better agriculture opportunities during the dry season. (Uphoff, Esman and Krishna, 1997). Social capital across sectors State, market and civil society can increase their effectiveness by contributing jointly to the provision of welfare and economic development. The success of this synergy is based on complementary rather than substitutable inputs, trust, freedom of choice and incentives of parties to cooperate (Evans 1996, Ostrom 1996). Plan Puebla (Mexico) is a joint project among farmer groups, university, government and private institutions to develop appropriate technology for farmers growing rain-fed maize. It has increased yields and incomes for almost 50,000 farmers, generated institutional changes and has been a model for other rain-fed agricultural programs (Uphoff, Esman and Krishna, 1997). (b) Rural development and social capital. Reducing rural poverty and hunger are two fundamental challenges. More than a billion people still exist in conditions of abject poverty. Most of them—more than 800 million—live in rural areas. Thus increasing the well-being of rural people and sustaining the improvements are key goals of most countries and all development agencies. Rural communities be endowed with land and water (natural capital), but they often do not have the skills (human capital) and organizations (social capital) which are needed to turn the natural resources into physical assets. Social capital is significant because it affects rural people’s capacity to organize for development. Social capital helps groups to perform the following key development tasks effectively and efficiently:

These four tasks must be done in order to sustain individual and community well-being (Uphoff 1986). (c) Urban development and social capital Urban areas, with their anonymity and fast pace, can be unconducive to societal cooperation. Social capital and trust are more difficult to develop and sustain in large groups (La Porta et al 1997). In many cases, interactions between parties are not repeated and therefore there is no incentive to develop reciprocal relations. In urban settings, people tend to cluster together in small communities and networks of support, but trust and goodwill for those outside immediate groups is minimal. High levels of intragroup social capital and very little inter-group social capital (referred to as "bridging social capital") may have profound effects on inequality, private sector development, government and public welfare (Schiff 1998, Putnam 1996, Fukuyama 1995). Nowhere is inequality more apparent than in urban areas where the rich and poor live and work in close proximity to each other, but rarely develop relationships. Housing and isolation Inequality is exemplified and sometimes exacerbated through housing. In most cities, housing separates people by income (Van Weesep and Van Kempen 1994). Many urban poor live in slums or ghettos which are physically isolated from business, health facilities and public transportation. The spatial isolation of the poor is compounded by social isolation. The rich and the poor rarely participate in the same activities, groups and associations. They do not have social ties to one another. Lack of connections to those with resources, both physical and otherwise, results in fewer opportunities for the poor. Spatial and social isolation – a lack of bridging social capital -- can lead to a cycle of poverty, i.e. children of poor parents have few or no opportunities to lift themselves out of poverty (Wilson 1987). Informal sector and safety nets Due to high unemployment rates and increasing urbanization, many poor cannot secure formal work in cities. In such cases, informal relations provide a crucial safety-net for the urban poor and improve their chances and quality of day-to-day survival. This is especially true when formal safety nets, such as health care and unemployment benefits, are nonexistent or extend only to the participants in the formal economy. Since 1972, the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in Indian cities has provided millions of women in the informal sector with assistance and a sense of security (Uphoff et al 1998). Decentralization and community organizations With increasing urbanization and decentralization in developing countries, city governments are facing new responsibilities. They must deal with an influx of people, most of whom are low-skilled and without capital resources or connections to job opportunities and without formal safety nets. Since most of the influx is poor people who may never work in the formal economy, cities do not receive additional finances through tax revenues comparative to their rising populations. When under-funded city infrastructure breaks down, such as schools, transportation and health facilities, there is increased potential for social disintegration. 5. Critical Analysis of the Definition (a) Social “capital”: a term that sounds very economic As noticed in the Infed website, “we need to be aware of the dangers of `capitalization`. As Cohen and Prusak have commented, not everything of value should be called `capital`. There is a deep danger of skewing our consideration of social phenomenon and goods toward the economic. The notion of capital brings with it a whole set of discourses and inevitably links it, in the current context, to capitalism.” In this way, we can wonder how, but also why, all social ties and relations could and should be measured. When already land and water, but also a house, are far from being only marketable products, but may represent a whole life and be the centers of human relations for a determined community, social ties and relations cannot be considered as measurable assets. This terminology leads to see in the previously quoted websites tendencies to go over immeasurable daily relations that people naturally always have built, from short term occasions to life-long relationships, to concentrate on those that are or have become formalized, and therefore measurable, through participation to associative and political life, and belonging to all kind of groups. Activities of State authorities, private and international agencies and organizations are also put forward, but can we really call “social capital” a World Bank or governmental program, even if it claims being based on the beneficiaries’ participation? (b) The example of rural communities On its page on rural development and social capital, the World Bank “Rural communities may be endowed with land (natural capital), but they often do not have the skills (human capital) and organizations (social capital) which help turn natural resources into physical assets and protect those assets from degradation. Social capital is significant because it affects rural people’s capacity to organize for development. Social capital helps groups to band together to raise their common concerns with the state and the private sector.” That social capital helps rural communities, through groups representing their interests, to raise their concerns and defend themselves is definitely true, but have they waited for urban-based engineers and organizations to know how to make the most of their lands? Scientific researches also certainly have helped some productions to be more effective, at least in some cases and without counting all the negative impact on environment that some have had, but this has nothing to do with social capital. On the contrary, what about the natural mutual assistance that people in rural areas, as well as indigenous peoples in general, always have developed spontaneously to cope with high work seasons, and face consequences of bad weather, animal epidemics, and other hardships? (c) Keeping informal human relations in mind Besides the rural example, the experiences of social production of housing as reported from Latin America show poor communities naturally building social relations—and as such “producing” social “capital” according to the jargon employed if not overused in the quoted websites—to improve their living conditions. Their struggle consists then in having their efforts formally recognized, and make sure that the authorities will not evict them and tear their houses down because of lack of building permits or location in slum areas among other pretexts. Contrarily to what is mentioned above related to urban development and social capital, even if wealth inequality brings social isolation, in most cases poor people do not rely on the rich to try to improve their living conditions anyway. Many programs of international agencies claim to do so, but at best only consult the so-called beneficiaries, forgetting that they may already have developed alternative solutions to their situation, and in all cases know better the context and what they need than the program designers. 6. Readings Recent articles/books by Robert D. Putnam and/or Thomas Sander: 1. Better Together, The Report of the Saguaro Seminar: Civic Engagement in America, 2002, at http://www.bettertogether.org/pdfs/bt_1_29.pdf, http://www.bettertogether.org/pdfs/bt_30_87.pdf and http://www.bettertogether.org/pdfs/bt_88_100.pdf 2. Putnam, Robert D. "The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life", in American Prospect (spring 1993); 3. Putnam, Robert D. "The Strange Disappearance of Civic America," in American Prospect 4. Putnam, Robert D. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital”, in Journal of Democracy (1995); 5. Putnam, Robert D. ”Community-based social capital and educational performance” in Making Good Citizens: Education and Civil Society, edited by Diane Ravitch and Joseph Viteritti, New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2001; 6. 7. Putnam, Robert D. Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society, Oxford University Press, 2002 8. Putnam, Robert D. Foreword for volume of Housing Policy Debate on social capital, Housing Policy Debate, Volume 9, Issue 1 (1998); 9. Putnam, Robert D. Making Democracy Work (Princeton: Princeton University, 1993); 10. Robert D. Putnam and Lew Feldstein, Better Together: Restoring the American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, September 2003); 11. Sander, Thomas and Robert D. Putnam, “Schools and Social Capital,” School Administrator (September 1999); 12. Sander, Thomas with Lewis Feldstein, “Community Foundations and Social Capital”, in Peter Walkenhorst, ed., Building Philanthropic and Social Capital: The Work of Community Foundations (Bertelsmann Foundation Publishers, 2001); 13. Sander, Thomas, coeditor. “Encyclopedia of Community: From the Village to the Virtual World”, Sage Reference (2003); 14. Sander, Thomas. “Social Capital and New Urbanism: Leading a Civic Horse to Water?” National Civic Review, vol. 91, issue 3 (fall 2002); 15. Sander, Thomas. Putnam, Robert D. “Walking the Civic Talk after September 11” (Op-Ed), Christian Science Monitor (19 February 2002 ); Other authors: 16. Baker, Wayne E. Achieving Success Through Social Capital: Tapping Hidden Resources in Your Personal and Business Networks (Milwaukee WI: Jossey Bass, 2000); 17. Baron, Stephen, John Field and Tom Schuller, eds., Social Capital: Critical Perspectives (Oxford: Oxford University, 2000); 18. Berry, Jeffrey M., Kent E. Portney, and Ken Thomson, The Rebirth of Urban Democracy (Washington: Brookings Institution, 1993); 19. Bhattacharyya, Dwaipayan, Niraja Gopal Jayal, Bishnu N. Mohapatra And Sudha Pai. Interrogating Social Capital (New Delhi: Sage, 2004); 20. Blakely, E. J. and Synder, M. G, Fortress America: Gated communities in the United States (Washington: Brookings Institute, 1997); 21. Bourdieu, Pierre. “Forms of capital,” in J. C. Richards, ed., Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (New York: Greenwood Press, 1983); 22. Briggs, Xavier de Souza. "Social Capital and the Cities: Advice to Change Agents." National Civic Review 86, No. 2 (summer 1997), pp.111–18; 23. Buchanan, Mark. Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Science of Networks (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002); 24. Coleman, J. C, “Social capital in the creation of human capital,” American Journal of Sociology , no. 94 (1988), pp. S95–S120; 25. Coleman, J. C. Foundations of Social Theory (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); 26. Collier, Paul. "Social Capital and Poverty" (Washington: The World Bank (mimeo), 1998); 27. Edwards, Bob, Michael W. Foley and Mario Diani, Beyond Tocqueville: Civil Society and the Social Capital Debate in Comparative Perspective (Civil Society) 28. Ehrenhalt, Alan. The Lost City: Discovering the Forgotten Virtues of Community in the Chicago of the 1950s (New York: BasicBooks, 1995); 29. Evans, Peter, "Government Action, Social Capital and Development: Reviewing the Evidence on Synergy," World Development vol. 24, no. 6 (19996), pp. 1119–32; 30. Fukuyama, F. The Great Disruption. Human nature and the reconstitution of social order (London: Profile Books, 1999); 31. Fukuyama, Francis, "Social Capital and the Global Economy," Foreign Affairs vol. 74, no. 5 (1995), pp. 89–103; 32. Gladwell, Malcolm. "Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg," New Yorker (11 January 1999), http://www.gladwell.com/1999/1999_01_11_a_weisberg.htm; 33. Grootaert, Christiaan "Social Capital: The Missing Link?" Expanding the Measure of Wealth: Indicators of Environmentally Sustainable Development (Washington: The World Bank, 1997); 34. Hanifan, L. J. “The rural school community center,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 67 (1996), pp. 130–138; 35. Hanifan, L. J. The Community Center (Boston: Silver Burdett, 1920); 36. Knack, Stephen and Phillip Keefer, "Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country Investigation," Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (1997), pp. 1251–88; 37. Mayer, Peter. The Wider Economic Value of Social Capital in South Australia (Adelaide: Office for Volunteers, 2004); 38. Moser, Caroline and Jeremy Holland, "Urban Poverty and Violence in Jamaica," (Washington: The World Bank, 1997); 39. Narayan, Deepa and Lant Pritchett, "Cents and Sociability: Household Income and Social Capital in Rural Tanzania," Economic Development and Cultural Change (1998); 40. Ostrom, Elinor and James Walker, eds., Trust and Reciprocity: Interdisciplinary Lessons for Experimental Research; 41. Ostrom, Elinor. "Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy and Development," World Development vol., no. 6 (1996), pp. 1073–87; 42. Ridley, Matt, The Origins of Virtue: Human Instincts and the Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Penguin Books, 1997); 43. Robison, Lindon and Marcelo Siles, "Social Capital and Household Income Distribution in the United States: 1980–1990," Michigan State University, Department of Agricultural Economics, Report No. 545 (1997); 44. Rotberg, Robert. Patterns of Social Capital : Stability and Change in Historical Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2001); 45. Saegert, Susan, J. Phillip Thompson, Mark R. Warren, Social Capital and Poor Communities [Ford Foundation Series on Asset Building] (New York: Ford Foundation, 20010); 46. 47. Schecter, Jr. "Building Community with Social Capital: Chits and Chums or Chats with Change,", National Civic Review vol. 86, no. 2 (summer 1997), pp. 129–40; 48. Schiff, Maurice, “Social Capital, Labor Mobility, and Welfare: The Impact of Uniting States," Rationality and Society, vol. 4, no. 2 (1992), pp. 157–75; 49. Sennett, R., The Corrosion of Character. The personal consequences of work in the new capitalism (New York: Norton, 1998); 50. Sirianni, C. and Friedland, L. (undated) “Social capital,” Civic Practices Network, http://www.cpn.org/sections/tools/models/social_capital.html; 51. Temple, Jonathan, "Initial Conditions, Social Capital, and Growth in Africa," Journal of African Economies, vol. 7, no. 3 (1998); 52. The World Bank, “What is Social Capital?” PovertyNet, (1999), http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/scapital/whatsc.htm 53. Vanourek, Gregg, Scott Hamilton, and Chester Finn, "Is There Life After Big Government?: The Potential of Civil Society," The Hudson Institute; 54. Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady, Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1995); 55. Walzer, M., On Tolerance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997); 56. Walzer, Michael, "Civility and Civic Virtue in Contemporary America," in Radical Principles: Reflections of an Unreconstructed Democrat (New York: Basic Books, 1980); 57. Walzer, Michael, "Idea of Civil Society," Dissent, (spring 1991), pp. 293–304; 58. Watts, Duncan J. Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003); 59. Wilson, William Julius. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor, New York: Knopf, 1996); 60. Woolcock, Michael, "Social Capital and Economic Development: toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework," Theory and Society vol. 27, no. 2 (1998), pp. 151–208. Books and articles that are more critical of toward the social capital concept and theory: 61. DeFilippis, James, “The Myth of Social Capital in Community Development,” Housing Policy Debate, vol. 11, issue 4 (2001); 62. Edwards, Bob, Michael Foley and Mario Diani, eds., Beyond Tocqueville: Civil Society and the Social Capital Debate in Comparative Perspective (Boston: University Press of New England, 2001); 63. Lemann, Nicholas, "Kicking in Groups," Atlantic Monthly (April 1996), pp. 22–24; 64. McLean, Scott L., David Schultz and Manfred B. Steger, eds., Social Capital: Historical and Theoretical Perspectives on Civil Society (, 2002); 65. Portes, Alejandro & Patricia Landolt. "The Downside of Social Capital,” The American Prospect 26 (May–June 1996), pp. 18–21; 66. Sobel, Joel, ”Can We Trust Social Capital?”, in Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (March 2002), pp. 139–154.

Documents specifically related to Middle East and North Africa: 67. Assaad, Ragui. “Kinship Ties, Social Networks and Segmented Labor Markets: Evidence from the Construction Sector in Egypt,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 52 (1997), pp. 1–30: The construction industry in Egypt is examined to determine whether kinship ties and other social relationships determine a construction worker`s choice to learn a specialized craft. A theoretical model which includes variables such as kinship ties, region of origin, and education is developed. The author finds some evidence that social networks can promote segmentation in the construction industry. 68. Bayat, Asef. “Activism and Social Development in the Middle East,” International Journal of Middle East Studies (2002), pp. 1–28: In this article, Bayat considers social activism and its relationship to social development in the Middle East. He examines the nature of grass-roots activism and the various strategies used by the region`s urban grass-roots to defend their rights and improve their lives today. In doing so he looks at six different types of activism expressed in urban mass protests: trade unionism, community activism, social Islamism, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and quiet encroachment. 69. Cunningham, Robert. “Fostering Community: A Significant Role for the Medina Souq,” Arab Studies Quarterly (December 1992), pp. 61–74: The souq in Medina, functions socially as a welfare system, a support system and a school of traditional behavior that displays paradoxical characteristics of action as well as constraint. The traditional market or Souq, ostensibly exists to provide a location for distribution of goods and services. Studies show that it fosters social networks that contribute to political influence. Though it does not influence any decision making in the city, it functions socially as a welfare and support system as well as a school of social behavior. It helps form an atmosphere of opposing ideas like individual freedom and community bonding, competition and cooperation etc. that even help ameliorate tensions that arise from social change. 70. Ibrahim, Saad Eddin, “Reform and Frustration in Egypt,” Journal of Democracy, vol. 7 (October 1996): Economic reforms in Egypt have not been rapidly adopted for fear of alienating the poor and middle class. The political, social, and economic conditions in Egypt are related and interdependent. Economic policy calls for converting state run sections of the economy to private ownership. Converting public sectors to private ones may disrupt employment and increase the appeal of Islamic militancy. 71. Mernissi, Fatema, “Social Capital in Action: The Case of the Aït Iktel Village Association” (12 May 1997), www.worldbank.org/wbi/mdf/mdf1/socialcp.htm: This paper examines the effectiveness of social capital in Arab cultures. Using the Aït Iktel Village Association, this paper demonstrates the effectiveness of social capital in creating community initiative and limiting the state`s role in water, sanitation, health and education. 72. O`Brien, David, Andrew Raedeke and Edward Hassinger, “The Social Networks of Leaders in More or Less Viable Communities Six Years Later: A Research Note,” Rural Sociology Vol. 63, No. 1 (March 1998): This paper studies five rural communities to see if rural communities with higher social capital have an advantage over other communities. The results suggest that there is a high degree of continuity in relative viability of communities in relation to their social capital. 73. Olmsted, Jennifer, “Women "Manufacture" Economic Spaces in Bethlehem,” World Development, Vol. 24, No. 12 (1 January 1996): This research examines the differences between refugee and nonrefugee Palestinian women with respect to education and employment patterns in Bethlehem. A combination of socioeconomic and institutional factors have led to a gap between refugee and nonrefugee Palestinian women in terms of education and employment patterns. Nonrefugees clearly lag behind. The author finds that access to education and agricultural production opportunities are key determinates to income generation. 74. Sullivan, Denis, “Private Voluntary Organizations in Egypt: Islamic Development, Private Initiative, and State Control,” (Miami: University of Florida Press, January 1994): The role that private voluntary organizations are playing in challenging the governments role in promoting economic development and threatening the legitimacy of the current regime are explored. Private revolutionary organizations including Christian, feminist, capitalist and Islamic groups are challenging the role of the Egyptian State in promoting socioeconomic development. The state has been meeting this challenge by pursuing various new approaches to government. Private revolutionary organizations have been working within the system to try to change it rather than outside the system. The pressure they have been putting on the government poses a challenge which will likely force the government to reform itself and open itself up to greater participation, democratization and economic restructuring. 75. Wainryb, Cecilia and Elliot Turiel. “Dominance, Subordination, and Concepts of Personal Entitlements in Cultural Contexts,” Child Development, vol. 65 (January 1994): Individualistic as well as hierarchical types of cultures are heterogeneous with respect to attitudes towards personal entitlement. Taking samples from two diverse cultures, one structurally rigid in the social duties context , the other, more autonomous in the same regard helps to form a perspective on personal entitlement in both. Both are amenable regarding moving towards the other end of the spectrum as against their positions in the past. Thus, heterogeneity in personal entitlement is an attitude that shows in stricter, hierarchical cultures as well as their liberal, individualistic counterpar |

||||||||||||

Social Capital:

© 2021 All rights reserved to HIC-HLRN -Disclaimer